WOMEN OF BANGALORE

In the middle of Olympe Ramakrishna’s exhibition of portraits rests an unshakably hypnotic gaze that pierces our presence with foreboding seduction. This is Sneha’s portrait, fashioned after the French painter Bernard Boutet de Monvel’s uniquely famous painting of Yashwant Rao Holkar, the Maharaja of Indore. Sneha’s figure arrests our attention, disarming us with disquieting ease. Garbed in a traditional Maratha attire, replete with a garnet-hued turban on her head and exquisite jewelry adorning her chest, Olympe’s brush sheaths Sneha in a stately aura of strength and discipline; an evocation that requests—nay, requires—our immediate attention. Awash with the regal colour burgundy, Olympe’s hand emphasises on Sneha’s person with an otherworldly solemnity, a seriousness that parallels the sitter’s life as a lawyer, while simultaneously impressing upon the viewer a decidedly human touch—of care, of concern, of love. This is where Olympe’s art truly comes into its own, flirting between the realms of the real and the ethereal; it is the making of a symphony of colours that luxuriously seats us on the white throne of the Holkars, while keeping a razor-sharp sabre at the ready.

For the Franco-Indian artist based out of Bangalore, this in-betweenness has been increasingly autobiographical. “Whenever I’m travelling to France these days, visiting my home, displaying my works,” Olympe shares candidly, “a part of India always remains with me.” Today, Olympe’s art finds itself at a unique precipice. Born a Norman, the artist spent close to a decade perfecting the human form, studying drawing and painting at the Beaux-Arts, the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, the Atelier Artmedium, and the Battersea Art Center in London—an education that kept Olympe rooted in the weighty academic expression of European artists like Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Henri Rousseau, and Paul Gauguin. The muted surreality of Rousseau’s landscapes or Ingres’ neoclassical paintings, however, was soon to be married with the flashy zest of Francis Newton Souza’s daring figures, Maqbool Fida Husain’s passionate horses, and Amrita Sher-Gil’s tender portraits.

An earthy and sedate palette of deep hues became combined with brighter shades of reds, browns, and yellows; a combination that is explicitly visible in the portraits on display. Far from being liminal and ambiguous, Olympe’s craft, much like that of Sher-Gil’s (an artist who Olympe is dearly fond of), has realised a unique cultural richness thatbrings the East and West together, an assertive myth-making that has become an underlying pursuit for the artist.

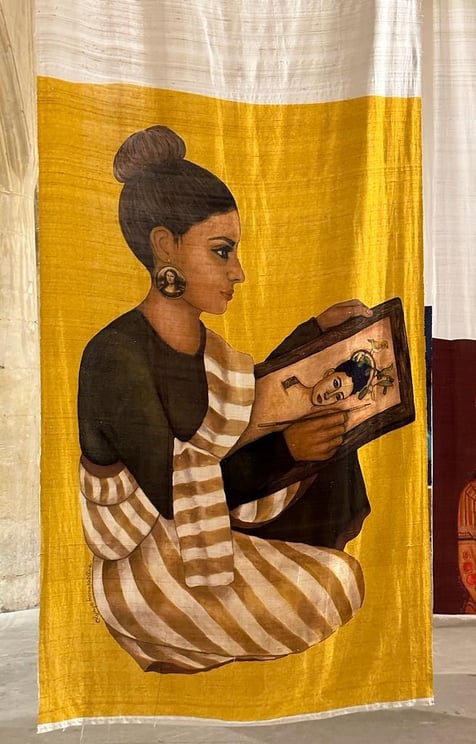

This conscientiousness to remain deliberately cosmopolitan is observed closely in Olympe’s self-portrait; mirroring the unassuming depictions of court painters like Bishandas, Bichtir, and Daulat from the Persian and Mughal manuscript painting tradition, Olympe presents herself with a formal and assertive side profile, working on Charisma’s portrait. As a diligent court painter from the ateliers of Akbar and Jahangir, draped in white-and-ochre stripes and adorning an earring depicting Leonardo da Vinci’s painting Mona Lisa (a innocent play on Olympe’s son, Leonard), the artist’s hand rests assured, detailing the sitter’s features. Olympe introduces us to a portrait-in-a-portrait-in-a-portrait; or a portrait of a time—we are

made aware of the European painterly tradition (seen in Charisma’s in-progress portrait), the medieval painting tradition that defined the larger part of the Indian subcontinent (Olympe’s self-portrait), and a little easter-egg for the artist’s son

(the Renaissance-period Mona Lisa).

Olympe’s series of portraits form a Muraqqa, an album of paintings stitched together to convey a singular truth: the divinity of the feminine perspective. By highlighting eleven of the artist’s acquaintances and confidants from the ascending middle-class in Bangalore, Olympe’s art—filled with signs and symbolisms—provokes a deeper, in-depth understanding of the diverse

experiences that inform femininity and its universality across geographies of time and space. Chandu’s portrait does this with great regard: draped in a bohemian blue dress, Olympe poses Chandu as Raja Ravi Verma’s goddess Lakshmi, with two of her hands extended in the abhayamudra, providing protection and dispelling fear, and the varada mudra, granting boons and

remaining generous.

Chandu’s metaphor extends itself to the entire series, visualising a noticeably changing society that, yet still, remains committed to honouring its traditions, its histories, its roots. Moreover, Chandu’s mudras are not superficial, but intercede into our lives with great nuance, advocating for a more liberated and powerful understanding and representation of femininity.

Olympe’s muses are a far-cry from the passive, objectified ‘grande odalisque’ of Ingres or Goya; instead, their characters are powerfully staged, built upon, and exalted—this is Olympe, imbibing the spirit of Édouard Manet’s Olympia, a spirit that (re)claims control, and gazes back at us.

The deliberate avoidance of any background in the paintings foregrounds Olympe’s formal, compositional, and symbolic enquiries. By placing the highly-detailed depictions of the artist’s muses against flat, bold, and strong colours, Olympe suspends each of the eleven women—Lux, Roopashree, Romi, Shuchika, Charisma, Kavitha, Chandu, Arpitha, Sneha, Hitha, Deepti—and herself, on a surface that elevates their position, their presence, their feelings.

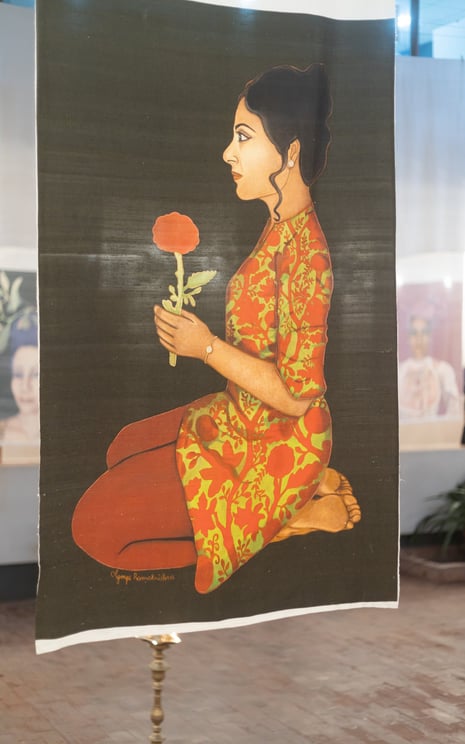

By invoking theuniversality of colours, the artist registers the universality of the cosmos; her art becomes symbolic of pranamu, or the life-force that channelises through every being of the natural and the preternatural world. In the midst of this primordial and phantasmic energy, Olympe’s muses stand apart as mother goddesses. Arpitha’s portrait, a glaring passion of the colour red, is adorned with a crown of pomegranates, a fruit that has symbolised sanctity, fertility, and abundance since the beginning of time. Arpitha’s brooding gaze approaches us with a mystical tension; an unease that makes itself alarmingly felt with Olympe’s bold colour palette. It is a colour palette that immediately centers our attention onto the pomegranate held in Arpitha’s right hand. Is she holding an unassuming fruit, or something more? With Olympe, symbols reign supreme, and it is not difficult to imagine Arpitha as Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, or Jesus Christ—the Saviour of the World, holding the celestial heaven in his hand; the pomegranate becoming the very womb of the world. If so, is Arpitha wearing a crown of thorns? While Olympe’s enigmatic mysticism leaves the ardent viewer scurrying for clues, some of her portraits are consciously biographical, and playfully direct.

Charisma’s portrait features a little bird perched on the branch of a jackfruit tree, placed against the sitter’s braided coiffure. The seemingly eccentric choice, however, is avowedly personal for the artist: it is for Olympe’s love for nature, for the symbolisms that characterise botanical (and largely, the Company School of painting) art, that the artist chose to incorporate Sheikh Zain al-Din’s ink-and-colour work Black-hooded Oriole and Insect on Jackfruit Stump in Charisma’s portrait.

Lux’s portrait, in a similar vein, features a vine of Seemal, or a cotton tree flower (it is interesting to note Olympe’s

concern regarding the symbolic flora, a flower that the artist chooses to place against a solid grey of Lux’s hair, deliberately deciding to forgo any texture so as to accentuate the ornament). “I like visiting the Lalbagh Botanical Garden; not necessarily to paint, although I do paint en plein air on my terrace, but to seek inspiration in the flora and fauna that surrounds us,” remarks Olympe.

The exhibition curates Olympe’s series of powerful portraits as digital prints that are suspended from the top, fluttering on large-scale dupion silk panels; panels that reminisce upon one of the most ubiquitous garments of Indian society, the sari. Olympe’s visuality and display design allows these women to float around in the gallery; a soaring presence that imbues our viewing experience with a sense of atmosphere and delight. The visitor is thrust onto a maze of sensuality and tradition—of femininity par excellence—navigating a familiar sight of saris on display, of women on the streets, mobile, and with purpose.

It is against this very bright and simple background that the keenly wrought details of Olympe’s art—as well as her

philosophy—become absolute. “My work has a precision that is easily observed. It is rigid, not in movement, but in the straight lines that accentuate structure and discipline in the figures I paint.” For the curious onlooker, Olympe’s art presents one final question: why are her figures so solemn in their facial expressions? In the end, her undulating colours stand for the ambivalent

and complex atmosphere of a rising superpower—of India, and its people—as much as they celebrate the joy of femininity.

Encountering Olympe’s muses, and the artist herself, allows us to reflect on our own presence, on our own resilience to make sense of a rapidly advancing society that is hurtling itself from one generation to another in a matter of centuries, decades, years, and soon, in days and seconds. And, in the end, the women of Bangalore reflect the tireless simplicity

of Olympe Ramakrishna’s artistic pursuit; a pursuit that is keen for its love of the feminine, and for the continuous desire to make art.

“Tomorrow I will start the art school’s work I paint at home and the fruit of my hard work is a very beautiful still-life”

Amrita Sher-Gil, in a letter to Victor Egan, February 1931.